One of the strongest drivers of genealogical research is the satisfaction of retrieving people who have been forgotten or deliberately written out of official history. That sense of righting historic family wrongs is powerful and addictive.

Here are two stories to illustrate why.

One famiy’s 1911 census return listed a 16-year-old son who had disappeared completely from family stories. It turned out he had enlisted in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers in 1915, and somehow survived Ypres, gas attacks and three solid years fighting in the British Army on the Western Front. But the Ireland he came back to in 1919 had changed completely. His family, now staunch Republicans, refused to have anything to do with him. So he moved to England and broke off all contact. Three generations later, his English grandchildren were tracked down and reintroduced to the wider family.

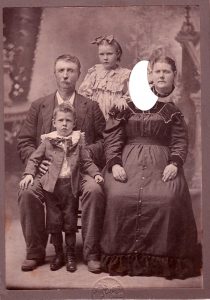

In another family, the only surviving photograph of one set of great-grandparents had a bizarre flaw. Where the great-grandmother’s face should have been, there was only a blank disk. Someone had very deliberately cut her from the picture.

For years, the family wondered what it was she had done to deserve such obliteration. Then a genealogist sifting through a deceased second cousin’s attic came across a locket and realized the photo it contained was the missing face.

Far from trying to eradicate her memory, one of her children had taken the piece of the picture to remember her by. And now her face was restored to the photo and became visible for the first time to her descendants.

Those of us who give genealogical advice sometimes joke that the job is equal parts genealogy and psychotherapy. But the healing provided by family restorations like these is genuine.